Three Ways to Support Clients Who are Oppressed

- Paulina Toledo

- Oct 30, 2024

- 8 min read

Updated: Oct 30, 2024

When working with clients who are experiencing trauma, as therapists, we must acknowledge the narrow and Westernised view of what trauma is currently considered within our field. The DSM-5-TR currently includes only post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and acute stress disorder. For these to be diagnosed, a person must have been exposed to threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence either directly or indirectly (6). However, the diagnosis of these disorders is inherently Western and focuses more on the experiences of war veterans, police officers, ambulance officers, and survivors of domestic and/or sexual abuse. In this way, the DSM-5-TR fails to acknowledge other forms of trauma like complex PTSD, Racial Trauma, and where trauma may be ongoing.

To be a therapist working with Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (BIPOC) and/or marginalised clients means understanding the systems of oppression in which our clients live. Our clients will experience marginalisation and oppression in the most benign of places; shopping centres, school classrooms, walking down the street, while commuting, when at work or social events, and so on.

For our marginalised clients, these daily events will spur feelings of anxiety and stress. The individual and communal experiences of racism that BIPOC are faced with, can lead to racial trauma and race-based traumatic stress. Symptoms of this can include; nightmares, headaches, flashbacks, avoidance, hypervigilance, disruption to the nervous system, questioning of identity, affect regulation, and trust issues (3) (8).

The cumulative stress of racially charged experiences and the daily reminders of how these occur play a big part in our client's mental and emotional wellness. In effect, because systems of oppression and their daily consequences are rarely acknowledged, our clients will, more often than not, internalise these experiences and start to believe in the negative depictions of their racial groups (1).

Regrettably, the mental health challenges stemming from social conditions and oppression, such as Racial Trauma, are frequently overlooked and undervalued by mental health institutions, which tend to prioritise individualised diagnoses (8). This means the focus is on “What is the problem within the client” and “What is the problem with the client's perception of the world?”. This places the issue within the client, rather than acknowledging collective racism and oppression as a social issue. When individuals reduce oppression to mere personal bias, they allow themselves to ignore the pressing crisis of persistent structural dehumanisation (3).

The question is then, how do we support our clients who experience oppression when the system of oppression denies its existence?

BROACHING

Broaching refers to the counsellor's intentional efforts to discuss how race, ethnicity, and culture impact the client's presenting concerns (5). Broaching can create a socially just counseling relationship as it provides transparency within the dynamic and attempts to minimise the barrier of power through acceptance and appreciation of difference (11).

For broaching to be effective, safety and stabilisation within the counselling dyad must be established first. Conversations regarding identity and Racial Trauma cannot move forward if the client does not feel safe to explore this. The therapist must also examine their own identities and responses, particularly when Racial Trauma is being discussed (11).

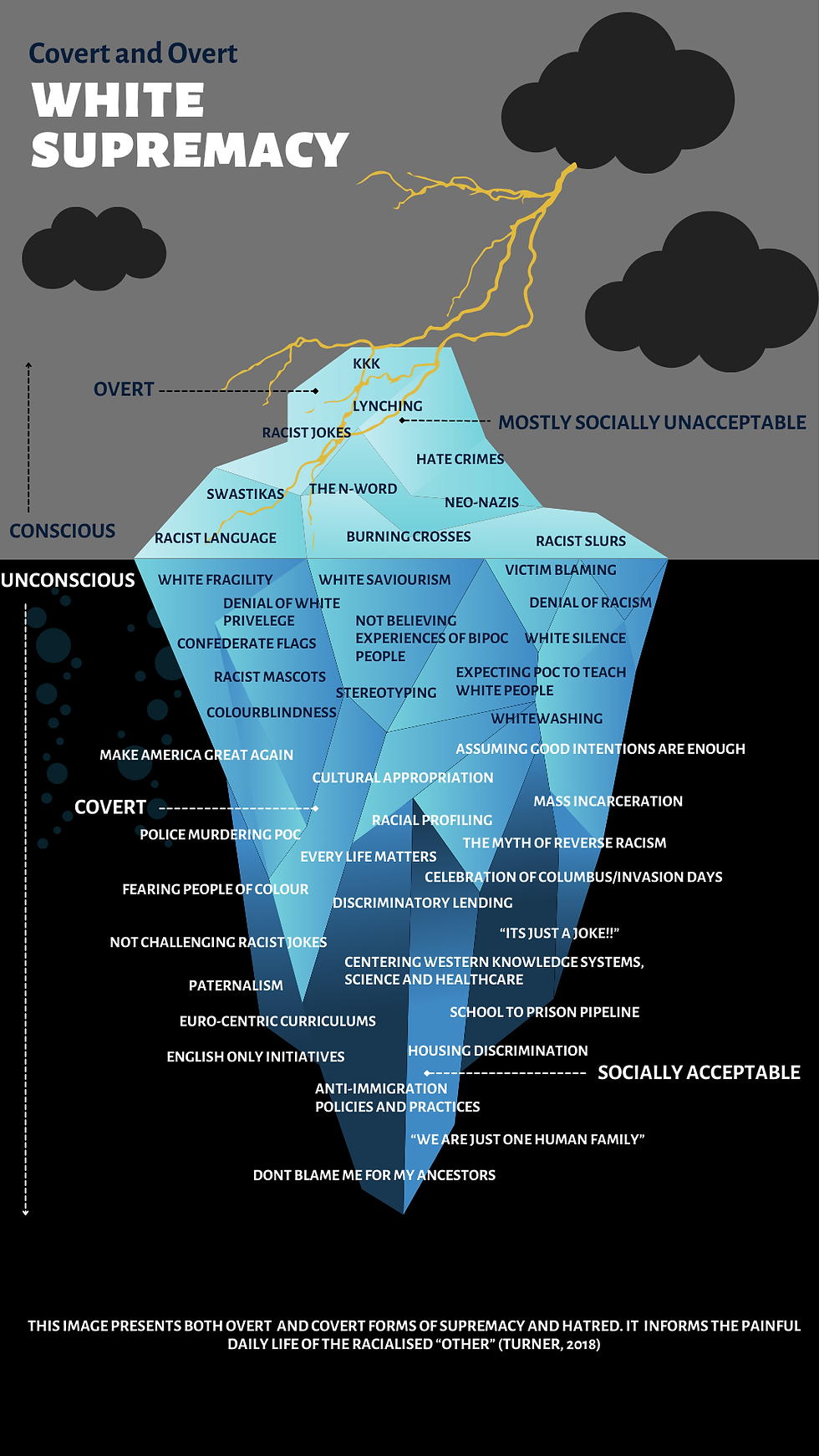

Acknowledging identity and culture validates clients' uniqueness while also acknowledging that white norms are not the norms for BIPOC and/or marginalised individuals. Through this examination, therapists and clients can collaborate equally to dismantle white supremacy (11) (see this related White Supremacy infographic.)

A specific set of considerations when broaching, has been developed by Day-Vines (4), and can be found on the Broaching infographic on our site.

CRITICAL CONSCIOUSNESS

Critical consciousness is about learning how to identify how systems of oppression contribute to experiences of racism and marginalisation. Engaging in critical consciousness decreases feelings of guilt and self-blame due to experiences of racism by widening the lens of critical thinking about structural oppression. It also promotes feelings of empowerment to resist these systems (8) (11).

Critical consciousness is a set of psychological and behavioural processes that include two elements:

Critical Social Analysis which is the ability to identify and critique the structural roots of oppression, and

Critical Action which is the involvement in individual and collective actions that challenge the sociopolitical status quo.

Critical consciousness is an ongoing process. It requests a therapist to continuously increase their own critical consciousness, so that they can then support the development of a client's critical consciousness. It is a valuable intervention when working with BIPOC clients. In saying that, however, it’s hard to support a client’s critical consciousness if you do not also engage in reflexivity and develop a critical consciousness for yourself both personally and professionally (8).

To support the development of your own critical consciousness, ask yourself questions like;

In what ways have I benefited from oppressive systems?

What systems am I a part of or supporting that may perpetuate oppression?

What privileges and power do I have?

Have these powers and privileges changed during my lifetime? How?

How am I prepared to be an agent of change to support the dismantling of these systems?

Enhancing your awareness entails cultivating a nuanced understanding of how structural racism manifests not only in counseling, but also across various systems. These include legal, educational, welfare, housing, immigration, and healthcare sectors, all of which claim, often falsely, to operate with universally beneficial intentions (11). Examining law enforcement, police brutality, and the higher incarceration rates of BIPOC in jails, may reveal startling anomalies.

Police brutality towards racial and ethnic minorities serve as a constant reminder of how white people assert their power and privilege over non-dominant groups (11). Some statistics to consider in this area include that First Nations men are 17 times more likely to be incarcerated than non-First Nations men while First Nations women are 25 times more likely to be incarcerated than non-First Nations women (you can read more about this at Closing the Gap). These statistics reveal the deep failures and resulting mistrust of systems that are supposed to be reliable and trusted, exposing the bias and deliberate oppression of people of colour. Helping clients recognise the injustice and racial bias within systems like this can help develop their critical consciousness. Critical consciousness can promote the transformation of the client, healing from Racial Trauma, and diminish internalised oppression, self-blame, and shame.

When developing critical consciousness with clients, ask questions like:

What systems perpetuate the oppression of people in general?

Have you thought about how your life has been shaped by oppression (school, work, socially)?

Are you aware of how oppression may impact you now or has impacted you in the past?

Who benefits from maintaining the status quo?

It can also be useful to look at the Power and Privilege Wheel (pictured below), and then examine collaboratively with the client where they are positioned. Note though, that it is important to use this wheel only when the client is in a safe position to do so, as it may reinforce feelings of hopelessness.

PROMOTING ETHNO RACIAL IDENTITY

ERI, or Ethnic Racial Identity, is defined as one's beliefs and attitudes about belonging to a given ethnic-racial group (13). ERI is a multidimensional phenomenon that consists of dimensions or attitudes and beliefs clients have towards their racial/ethnic groups and the processes by which clients develop these beliefs (12). Overall, research suggests that ERI and critical consciousness are assets in the lives of racially/ethnically minoritised clients because they work to buffer and protect clients from racism and oppression (2).

A recent study examined the protective role of ERI on the longitudinal effects of racism on Aboriginal Australian children's Social and Emotional Well-being (SEWB). Results showed that children with low ERI affirmation, whose parents reported they experienced discrimination/racism, were at an increased risk of poor SEWB two years later(8). This study also showed that promoting ERI affirmation can mitigate the effects of racism on the SEWB domains (8).

ERI has two dimensions:

Ethnic-Racial Identity Process which involves Exploration and Resolution. Exploration refers to investigating and learning one’s ethnic-racial group membership. Resolution refers to an individual sense of clarity and certainty regarding the meaning and role of these ethnic-racial groups in their lives (15).

Ethnic-Racial Identity Content which explores the beliefs about one's own ethnic-racial group and its relation to other ethnic-racial groups (14).

Among people of colour, ERI likely contributes to clients' understanding of, and engagement in, social movements like Black Lives Matter. The racialised experiences that inform clients' ethnic-racial identity may serve as an entry point for the growth of their critical consciousness (9).

The above techniques support a strengths-based approach, encouraging the client to look at their own resources and inner strengths. If therapists work to promote client’s own inner resourcing and the beauty of their existing connections to culture and community, the antidote for oppression will become easier to access when needed, as they only need to step into their own community.

(1) Adames, H. Y., Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y., Lewis, J. A., Neville, H. A., French, B. H., Chen, G. A., & Mosley, D. V. (2023). Radical Healing in Psychotherapy: Addressing the Wounds of Racism-Related Stress and Trauma. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 60(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000435

(2) Bañales, J., Mathews, C. J., Channey, J., Pinetta, B. J., Byrd, C. M., & Wang, M. T. (2024). A Preliminary Investigation of Longitudinal Associations Between Ethnic–Racial Identity and Critical Consciousness Among Black and Latinx Youth. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000674

(3) Bryant-Davis, T. (2023). Healing the Trauma of Racism and Sexism: Decolonization and Liberation. Women & Therapy, 46(3), 246–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2023.2275935

(4) Day‐Vines, N. L., Cluxton‐Keller, F., Agorsor, C., & Gubara, S. (2021). Strategies for Broaching the Subjects of Race, Ethnicity, and Culture. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99(3), 348–357. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12380

(5) Day-Vines, N. L., Wood, S. M., Grothaus, T., Craigen, L., Holman, A., Dotson-Blake, K., & Douglass, M. J. (2007). Broaching the Subjects of Race, Ethnicity, and Culture During the Counseling Process. Journal of Counseling and Development, 85(4), 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00608.x

(6) American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

(7) Jean, P. L., Lockett, G. M., Bridges, B., & Mosley, D. V. (2023). Addressing the Impact of Racial Trauma on Black, Indigenous, and People of Color’s (BIPOC) Mental, Emotional, and Physical Health Through Critical Consciousness and Radical Healing: Recommendations for Mental Health Providers. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 10(4), 372–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-023-00304-7

(8) Macedo, D. M., Smithers, L. G., Roberts, R. M., Haag, D. G., Paradies, Y., & Jamieson, L. M. (2019). Does ethnic-racial identity modify the effects of racism on the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal Australian children? PloS One, 14(8), e0220744-. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220744

(9) Mathews, C. J., Medina, M. A., Bañales, J., Pinetta, B. J., Marchand, A. D., Agi, A. C., Miller, S. M., Hoffman, A. J., Diemer, M. A., & Rivas-Drake, D. (2020). Mapping the Intersections of Adolescents’ Ethnic-Racial Identity and Critical Consciousness. Adolescent Research Review, 5(4), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-019-00122-0

(10) Middleton, T. J., Toole, K. M., Culpepper, D., Hughes, D. C., Parsons-Christian, E., & Dollarhide, C. T. (2023). Decolonizing & decentering oppressive structures: practical strategies for social justice in school and clinical counseling. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 10(2), 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2023.2237023

(11) Mosley, D. V., Hargons, C. N., Meiller, C., Angyal, B., Wheeler, P., Davis, C., & Stevens-Watkins, D. (2021). Critical Consciousness of Anti-Black Racism: A Practical Model to Prevent and Resist Racial Trauma. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000430

(12) Rivas-Drake, D., Pinetta, B. J., Juang, L. P., & Agi, A. (2022). Ethnic-Racial Identity as a Source of Resilience and Resistance in the Context of Racism and Xenophobia. Review of General Psychology, 26(3), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/10892680211056318

(13) Schwartz, S. J., Syed, M., Yip, T., Knight, G. P., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Rivas-Drake, D., & Lee, R. M. (2014). Methodological Issues in Ethnic and Racial Identity Research With Ethnic Minority Populations: Theoretical Precision, Measurement Issues, and Research Designs. Child Development, 85(1), 58–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12201

(14) Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Quintana, S. M., Lee, R. M., Cross Jr, W. E., Rivas-Drake, D., Schwartz, S. J., Syed, M., Yip, T., & Seaton, E. (2014). Ethnic and Racial Identity During Adolescence and Into Young Adulthood: An Integrated Conceptualization. Child Development, 85(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12196

(15) Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Yazedjian, A., & Bámaca-Gómez, M. (2004). Developing the Ethnic Identity Scale Using Eriksonian and Social Identity Perspectives. Identity (Mahwah, N.J.), 4(1), 9–38. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532706XID0401_2